An artform passed down through centuries, right into your hands.

Beeswax ornaments trace their origins to sixteenth-century Germany, where bakers—already accustomed to working with honey in their recipes—found a creative use for the surplus wax from their hives. Since candle making required large amounts of beeswax, bakers would set aside the wax during harvests, melting and pouring it into their candy or cookie molds for storage. When the wax hardened, it captured the delicate impressions of the molds, leaving behind a unique and lasting decoration for their homes and even their Christmas trees. This charming tradition crossed the Atlantic with German immigrants, taking root in eastern Pennsylvania by the late seventeenth century.

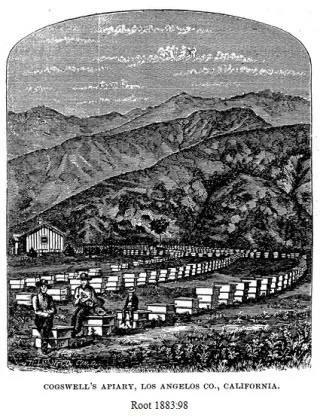

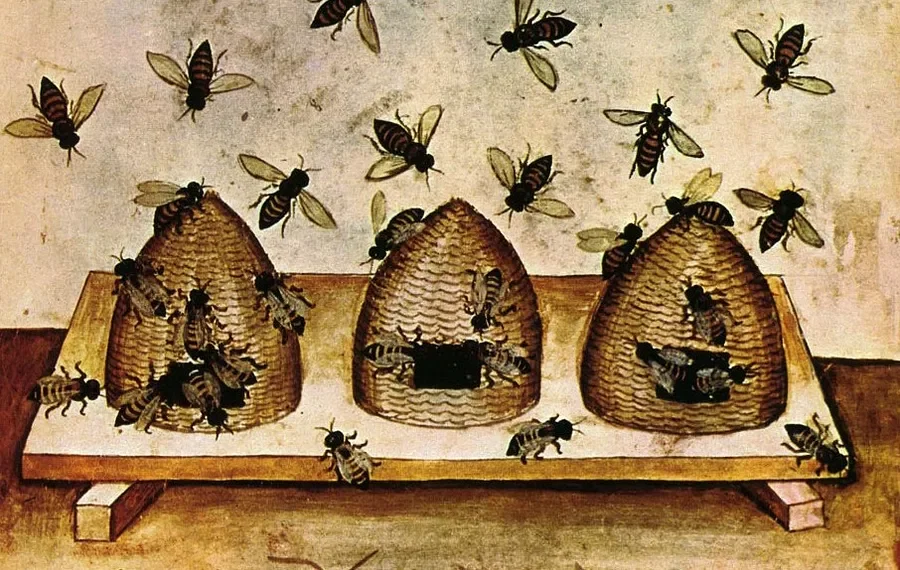

Honeybees themselves arrived in America even earlier, introduced to the Virginia colony in 1622. Although many today assume honeybees are native to the United States, they were brought here through the determination of early colonists. At the time, bees were kept in wooden boxes or straw skeps, and for the voyage across the Atlantic, ship hulls were lined with piles of sugar to keep them fed. Over the next century, honeybees spread through both human transport and natural expansion, eventually reaching every corner of the country and helping to establish a thriving agricultural and economic industry.

For colonists, beeswax was far more than just a candle-making ingredient. It was prized for its clean, bright flame at a time when most candles were made from smoky, foul-smelling tallow. Beeswax also found its way into everyday life: it was used to waterproof leather, seal letters with wax stamps, polish wooden furniture, preserve and lubricate tools, and even as an ingredient in early medicines and salves. In every colony, beeswax represented both practicality and refinement—a rare, natural material that blended utility with beauty.

Beyond its practical uses, bees and their wax also carried cultural and spiritual significance. One of the most enduring folk customs was the practice of “telling the bees.” Families believed that bees were deeply connected to the lives of their keepers and had to be informed of important events such as births, marriages, or deaths. If the bees were not told, it was feared they might stop producing honey, leave the hive, or even perish. Beekeepers would approach the hives to whisper the news, often draping them in black cloth during times of mourning. This custom, carried over from Europe, reflects the reverence and almost mystical bond humans have long felt with their bees.